Title On Employment and Wage-differential Structure - HERMES-IR

Title

Author(s)

Citation

Issue Date

Type

On Employment and Wage-differential Structure in

Japan : A Survey

Odaka, Konosuke

Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics, 8(1): 41-64

1967-06

Departmental Bulletin Paper

Text Version publisher

URL

http://hdl.handle.net/10086/8063

Right

Hitotsubashi University Repository

ON EMPLOYMENT AND WAGE-DIFFERENTIAL

STRUCTURE IN JAPAN= A SURVEY

BJ, KONOSUKE ODAT(A*

I . I ntrod uction

Post-war developments in economic growth and in unemployment problems present remarkable contrasts between Japan and some of the more advanced economies. While the

former has enjoyed a splendidly rapid growth and almost negligible unemployment, the latter

have at times suffered slackening rates of growth and even higher unemployment. It seems

as if Japan has indeed entered the "stage of mass-consumption," just as the United States did

in the 1920's. There may be an element of truth in such a view. When one probes more

deeply into the structure of the Japanese economy, however, it turns out that the analysis

of the phenomenon is far more intricate than it appears on the surface. In fact, one may

even become skeptical about the validity of a straig.'htforward comparison between the both

types of economies.

Of particular interest in this respect are the following three characteristics of the economy:

(1) The coexistence of an extremely low unemployment rate (in the neighborhood of 1

to 2 percent) and continued low incomes in agricultural, small business, and some

service sectors;

(2) Simultaneous presence of large- and small-scale firms in the manufacturing sector; and

(3) Several peculiar characteristics of the labor market, such as employment tenure, wide

vage differentials according to the size of the firm, enterprise unionism, etc.

One may note that these are in essence the featuring characteristics of the so-called "dual"

economic structure. The persistence of such "duality" is theoretically puzzling, and it naturally demands rationalization as well as careful investigation. "This is especially so," as one

specialist puts it, "if we look at the problem from the viewpoint of neo-classical economic

theory, since one of the messages of neo-classical theory is that differentials would tend to

disappear."I Among other things, the phenomenon of intra-industry wage differentials by size

of the firms seems especially fitting in describing the nature of the problem before us.

The purpose of this paper is to present a brief survey on Japanese employment mechanism.2

It should be understood at the outset that this is a problem-oriented survey; consequently,

its coverage of literature is not meant to be comprehensive. Section 11 will be devoted to a

discussion on the historical development of supply of labor, Section 111 to an analysis of the

relationship of Japanese industrial structure to the wage-differential structure, and Section IV

to a survey of selected literature on Japanese employment mechanism.

* Assistant (Joshu), Institute of Economic Research.

1 Leibenstein [u], p. 4.

z By "employment mechanism" we mean both behavioral and structural characteristics of the labor market.

42 HITOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF EcoNoMlcs [June

II. Sumply of Labor

la LewiS

According to Fei and Ranis, Japanese economic development passed the phase of "unlimited

supply of labor" at about the end of W W. I., since their data indicate that the aggregate

capital-labor ratio had begun to increase around that time.s In their words,

...in the course of a successful development effort, a capital-shallowing phase in the econo-

my's industrial sector will gradually give way to capital deepening. The turning pointor, perhaps more realistically, the turning range-occurs when diminishing returns to

labor-saving innovations are telescoped with the cessation of the phase of unlimited labor

supply .

In the case of Japan,...such a turning point occurred around 1916-19, Ieading us to

believe that her phase of unlimited supply of labor came to an end at about that time.1

As an independent substantiation of their claim, the authors point to the fact that real wage

rates in Japanese manufacturing industries showed an upward spurt in the 1910's.

Now, it is not easy to reconcile the rapidly rising real wage rates with an infinitely

elastic supply of labor. Moreover, most authors seem to be in agreement that the period

following W.W. I. marks a crucial stage in Japanese economic development, not only in terms

of the growth rate but also with respect to technological advance. On the other hand, however, a reexamination of long-term series of real wages for male workers in manufacturing

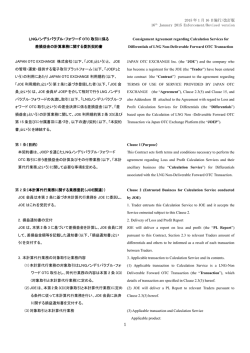

industries (shown in Figure I and Table l) indicate that there was a phase of wide "plateau"

in the 1920's and the 30's. Although the post-W.W. 11 data are not available for a comparable span of time, Umemura suspects that there will be another "plateau" after, say, 1955.5

FIG, l. REAL WAGES IN MANUFACTUI ING INDUSTRIES, 1899-1938

(MALE PRODUCTION WORKERS OF ALL AGES)

300

200 ( I914=100)

roo

90

80

70

: D*flated by th* cpl i*cl di*g h. se *e t.

' : D*flated by th* cpl excl*di g ho*=* re*t.

1900 1925 1930 1935

1905

1910

1915

1920

Sources: Money wages: Umemura-Minami es.timates; CPI: Yamada-Otani estimates

(for references, see Table I sources).

Fei and Ranis [4], [5] Ch. 7; the concept of "un]imited supplies of labor" was first developed by Lewis

[13]

Fei and Ranis [4], p. 304.

Umemura [5l], pp. 63-64.

1967]

ON EMPLOYMENT AND WAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN: A SURVEY

43

TABLE 1. A¥rERAGE ANNUAL RATES FOR MEN OF CHANGE 1N

MANUFACTURING REAL WAGES

Wages Using the

C. P.

1.

Rates of Change in Real

Period*

1899 ( P ) -1905 ( T ) **

1905 ( T ) -1913***

1913 -1920 ( P )

1920 ( P ) -1931 ( T )

1931 ( T) -1938 ( P )

* The periodization is due to Ohkawa-Rosovsky [32].

** 1899 is used in lieu of 1898.

*** The period of 1905-20 has been divided to two in order to make allowance for

the hyperinflation occurred at the close of W.W.1.

Sources : Money wage rates: Umemura'Minaml estimates; Consumer Price Index:

Yamada-Otani estimates. Both are taken from: K. Ohkawa, M. Shinohara and M.

Umemura, eds., Choki A'eizai T kei (Estimates of Long-term Economic Statistics of Japan

Since 1868), Vol. 8, Tokyo: ToyO Keizai ShimpOsha, 1967.

Admittedly it is awkward to rely solely on the behavior of wages in deciding whether or not

the "turnmg pomt" has been reached, Nevertheless, one might wonder how he would explain the presence of such "plateaus," if the "unlimrted supply" rs no more exrstent In

addition, it is also widely accepted that the economy retains, even up to the present, the

characteristics of a "dual" economy.

The presence of the duality may be illustrated by the nature of unemployment figures.

TABLE 2. THE PROPORTION OF UNEMPLOYED AMONG

THE MALE LABOR FoRCE*

* 15 years of age and over.

** In percentage points.

Source: S6rifu, Tokeikyoku (Prime Minister's Office, Bureau

of Statistics), R6d ryoku Ch6sa H6koku (Annual Report on the Labor

Force Survey).

44 HITOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF EcoNolYncs [June

Earlier we noted that the recorded level of unemployment is extremely low in contemporary

Japan. To illustrate the point, the percentage points of totally unemployed male adults (15

years and over) are shown in Table 2. However, we should be mindful of the fact that

Japanese unemyloyment statistics, as reliable as they are, are not readily comparable to those

of other nations due mainly to the existence of overemployment.6 For instance, even somewhat superficial observation of Table 3 is sufficient to impress one with the magnitude of the

TABLE 3. THE CoMPOSITION Ok* TnE MALE LABOR FORCE :

BY EMPLOYMENT S1'ATUS

* In ten thousands.

Source: SOrifu, Tokeikyoku (Prime Minister's Office, Bureau of Statistics). Rodoryoku Ch sa

Ho koku (Annual Report on the Labor Force Survey).

labor force under the categones of "self employed" and "unpaid family workers." Though

declining rapidly in proportion, overemployment is found both in manufacturing and in service

sectors, as well as in agriculture. If we may use the data for self-employed and unpaid family

workers as a proxy for this phenomenon, the following figures may help illustrate this point

(see Table 4).

It is well to bear in mind that overemployment is a structural (that is, inherent to the

structure of the economy), rather than a cyclical, phenomenon. Althoguh several alternative

explanations have been offered, its persistence seems best explained by the coexistence of the

technically advanced, "capitalistic" sector and the family-owned, "traditional" sector, the former

being operated under the profit maximizing principle, whereas the latter is aimed at, for instance, the maximization of total income.7

In the light of the above observations, one may be yet unpersuaded by the claim made

6 The phenomenon is commonly referred to as "underemployment" or "disguised unemployment."

However, "overemployment" is preferable, since it suggests a situation where more labor is actually

employed than the amount that marginal productivity indicates to be the equihbrium point. See Ohkawa

[30], p. 187 ff.

7 Ohkawa's argument is adopted here. See, for example, his [28], p. 210ff.; also. Gleason [6], pp. 64-80.

1967] ON ElvIPLOYMENT AND

rAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN= A SURVEY 45

TABLE 4. EMPLOYMENT STATUS OF THE MALE LABOR FORCE : BY INDUSTRY

(1962)

* In ten thousands. Percentage points do not necessarily add up to 100 due to rounding.

** Unpaid family workers.

Source: SOufu Tokelkyoku (Primc Ministcr's Offrce, Bureau of Statistics), R6d ryoku Ch sa

Ilokoku (Annual Report on the Labor Force Survey), 1962.

by Fei and Ranis without, at least, some qualifications. Furthermore, it may be possible to

present, and to test the validity of alternative explanations of the rising real wages in the

late 1910's and early 1920's such as:

(a) Rising relative importance of heavier industries and subsequent great shortage of

skilled labor;

(b) The economic boom due to the war, followed by downward rig'idity of money wages;

and

(c) The increase in agricultural productivity sufficiently high to sustain an improved

standard of living.

In short, the Japanese economy has been in a pseudo-equilibrium with sirnultaneous existence of overemployment of labor. The low level of unemployment is simply a reflection

of this condition. Sd long as such is the case, the condition of full emplooment in the neoclassical sense is not completely satisfied.8

III. Wage Dtfferential Structure9

For this economy it seems reasonable to differentiate industrial enterprises according to

their sizes. Not only are their external characteristics vastly different, but also their behavioral

pnnclples appear to be distmgurshable The coexrstence of the "mdustnal grants" with the

8 "Neo-classical" in the sense that unlimlted supply of labor is no longer available. See, e.g. Enke

[3] and Ohkawa-Minami [31] on this point. The Lewis model has been challenged by those who contend

that empirical findings may be consistently explained in the strictly "neo-classical" framework, without

appealing to such a dubious concept as unlimited labor supply. However, we shall not attempt at this

point to pursue this discussion any further.

9 The term "differential structure" was coined by Ohkawa and Rosovsky. See, e,g. their [27], pp. 77-83.

HITOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS [June

46

"less f ortunate

have

ones" has caught the attention of many scholars,]o Some preliminary analyses

revealed , for instance, that the capital turnover rate decreases, whereas both sales and

FIG. 2. SOME INDICATORS OF DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE

K

Thousand yen

2, OOO

N

1 , OOO

Y

ll

600

./' 1 V

.l

/ lw

(monthly)

./'

400

/

.J

i

Y

200

¥

. f )

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 Slze*

* In terms of capital asset; see footnote (11) for description.

Source : E. P.A. [9], pp. 152-53.

TABLE 5. SELECTED RATIOS DERIVED FROM INCOME STATEMENTS

OF MANUFACTURING FIRMS

* In million yen.

** Net working capital is the excess of the total current asset over the current liabilities.

Note: 1958 was a trough year; 1960 was approxlmately a midpoint of a peak-to-peak period.

Source: Okurasho (Ministry of Finance), Ho jin Kigy 'Fo kei Ne'np5 (Annual Statistical Report on Incorporated Firms), 1958 and 1960.

ro Researchs on this topic have been innumerable; for a comprehensive survey of the literature, see

Shinohara [40].

oN EMPLOYM. ENT AND WAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN: A SURVEY

47

safety margins generally increase, as the size goes up (see Table 5 for explanations). On the

other hand, no clear tendency is detected for the profit-asset ratio. It seems that the smaller

firms compensate their disadvantages, which are reflected in the above two margins, by the

high rate of capital turnover. The outcome of their effort is the roughly uniform rate of

yields on the invested capital.

But it is the existence of wide wage differentials which is particularly intriguing. As

Figure 1-2 displays, they move fairly parallel to average value productivity, with the gap

between them slowly increasing. In addition, it should be observed that capital intensity

(capital-labor ratios) moves up at a much faster pace than either wage or average productivity. 11

The problem of wage differentials is not particularly appealing from theoretical points of

view. In fact, economic theorists have long ignored this subject, thinking that it is only a

short-run phenomenon.12 Contrary to their expectations, however, there are various forms of

persistent wage differentials in developed economies such as the United States. Accordingly,

it was quite natural that after W.W. 11 monopolistic elements in the labor market caught the

attention of economists, who then were led to engage in the studies of wage differentials.13

Even at this stage, however, interfirm and interplant differentials have not been touched

upon frequently by American economists, making a striking contrast to the vast number of

researches undertaken in the areas of inter-industry, occupational, and geographical wage

drfferentials.1* The reason for the neglect is quite obvious: there seems little economic justification for such differentials to persist. If small firms exist in the market side-by-side

with larger establishments, despite various barriers to entry, it must mean that the smaller

companies own some unique advantages which make them capable of competing with larger

firms. The mere existence of the former indicates, according to this view, that their business

performance is satisfactory.15 Thus, there seems no a priori reason why there should be wage

ll The sizes are defined as follows (in million yen):

Only general patterns of the diagrms are relevant

or our discussion: In anlyzing these figures which

are classified by the size of the firm, one should not be concerned with minute details of ups and downs a]ong

the curves. The graphs are drawn on the interfirm basis and, as such, may quite naturally be expe cted

to register erratic movements. By the same token, one ought to be aware what he will get different

patterns depending on the methods of classification he adopts. This point was made earlier by Johnston

[8], pp. 110-35.

12 "Under the assumptions of neoclassical theory, such differentials either were presumed to be nonexistent or were considered to be short-run aberrations that disappear in the long run." (Lester [12], p. 483)

Is See, e.g. O.E,C.D. [26] for a listing of such studies.

14 Cf. Reynolds-Taft [37].

15 Steindl lists several reasons why small businesses survive under oligopolistic market conditions: differentiation in taste, force of habit, ignorance of relevant facts on the side of the consumers; goodwill

which is established between producer and customer; imperfection in the labor market (that is, exploitation

of wage earners); the oligopolistic condition itself: "the big firms which have estab]ished themselves as

price leaders there have in most cases little to gain from the elimination of small firms which account for

a small part of total supply." (Steindl [42], p. 60); and, finally, the gambling attitude of small enterprises.

We might add to this list a general economic growth which certainly helps to preserve the existence of

smaller firms and encourages their neiv entries. Parinthetically, the wide attention thai Steindl's book

has received in Japan attests to the keeness of the problem in the 'minds of the researchers. '

48

HITOTSUBAS田JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

》 H

N

4 F{

畑

σ》

o o

uつ

つ 一

一

ひqF輔 F→

oう

一

N 『尊

卜・ oつ

o

q o■ゆ cq

⇔

o

o

寸 一

〇 一

〇

oo o

Oq

つ 寸

o o

o

q o

う cつ

αD N

寸

oつ

斜

F→

0 0Q

マ

O r》

Fイ H

o

㎝

oう 一

、電 卜・

OD cq

0 0D

『守

H

も着瓢 o

OD αD

o o

卜

N

“

一

一

■蝦癩眉遇頴目の

ζつ q

り Q

D Oう

1 −

灯

oう

し》 』ミ

レ⊇ 口

oう H

r→

αD

Oう

→ rく

寸 『尋

σ》

卜A “

LQ

℃ ,

o oつ

00

“

マ

ト ー

リe“ マ

“

cq

N

O N

頃

o αD

o め

o o

cq り

N cq

oう 一

一 ト

oう

マ

『ぐ

・ oう

r→

→ r→

つ ト

・ ㎝

oう

一

う H

o oう

H

D O

》 cq

寸 αつ

寸 oO

−

cq αD

oつ

C“

‘ σ》

一

つ 一‘

N

ζつ q

o一 一

D Oう

σ》

一

N C噸

OσD マ

く9“ 眺

ζつ 』q

こつ 日

マ

くつ 』q

ζつ q

1℃q¢

06ε‘o駕きヌ帽︵℃’趣駕醤コペo包

bO

自 9一

可曽980一の角

[290口山£

卜

o⇔o−o︸︵^loH喫90邸 ﹂㊤10国包

喫の貸、器唱o邸ぺ9・嚇曽o撰o 軸賃喫o口 遷①喫鍵

ぜ》 o

■〇一邸h㊤畠oお目目︵にlo調樫言垂

05山貧“ぼε邸 一賜 ゆρ,の■醍離曇舅亀&㊤ 鳴 ミき’δ∫窪尋据q=哩認麗

℃①一 (一lo

の桝蝿.9日㊤一Q

一2Q

oz

寸

㊤qで国9 ハー ︵O ◎舌竃① 窯P‘ 貸o q ぺ一 ﹄邸三醤.営唱喫繋

o自7一謂詔日宕醍6黛﹄ 唱o障おいコqQ匹

㊤摺一×o↑

h旨一qりコ℃9一

一 eq oつ

bρ

ゆ

A

■ A

o一

o o

O

・ σ、

r→

㎝

8 鵠一《 一

Q ①

ζつ 日

寸 OD

一

ゆ

目

} oつ

A

2邸 o‘‘o℃90一自‘“o邸㊤9目 [’一 bO謂口⇔。一邸θ目.窪 ︵﹄ lo儀 哩首・^ 塁躯 §屋継

趣触聾.へo ミ リ﹄ .“o 知 o℃o 霜質一 〇㊤ “ 幅“﹄1 自語篭℃ ■趣口O① IO b鵡rコ熔調艶

‘一〇一〇“一①℃90一㊤目■一一〇 ︵鳴 ro日口喫臼旨 巽bρ弱勉.9臥婁言寵

⇔D【 目邸 (

o雪而q580

.O国日ρo<↑

喧 Qbつ一

oo

0D

cり

o

H

eq

ら oう

3

寸 寸

》 寸

A

Oq o

σ》 LQ

h

O 目

つ ト

8 鵠H 一

卜

』 の

』

①

o 卜O H7→ 一

N

O N

『守

H

OD

o

αD

く r吋

ζq

寸H H

》 N

》 寸

》 卜噂

ピ》 い噂

A

一

一

紬』か路鍾 H 口

眉㌍囲

賃邸αO

8bρ。63

図o℃唱H

o 卜

o ①

Oう

go

F‘

o

h

3

①

oo

乞鴇o目而の

oつ OD

} 卜

o 卜

z器①⋮⋮iσ5の

一 N

o oO

o o

ア→

q o

0 0Q

((の (

名器o賃dの

qDh A

o一 一

z 鴇 o ⋮⋮邸の

σ》 ooう ト甲

寸A 儀

o σ》

罷蕪自ζつ ﹄q

eq o

》 『尊

お角P︶︶誘專σ︾σ︾Hrrl

一

o o

Fく

寸o客鴇Φ⋮≡“の

旨 の

ロ ㊤

ち老口 o

O N

寸

a倉P︶︶ooうo寸σ︾σ︾Hrイ

o 寸

oo

αD

oo呂需①ε鳴の

卜 o

おeε︵おo①hP專專YY668800000り Q

甚一 H

o

くρ●H 一

罵ξ炉

卜 cq

めoz鴇㊤ε邸の

お倉P︶︶HOooσ︾σ㍉HH

o o

cq

e包丁86∴O IOLDHσ︶LDC織ζり ﹄q

σ》

一〇名鴇㊤9邸の

Ho渚器㊤Eioの

o 』D

((の (

{ 一

曲卦の噂 H ㊤

・3

の

一〇2;器oEi超の

聾HQqLDNら q

属㊤℃虞一

の①bo煽

r一Z国Σ鵠のコq身<﹄の口街○国N一の>自自の日<一臼㌧Z国名国編旨∩ 国O<3

︵.の.⇒㊤﹄廿﹄o︸論、属帽α娼h一〇︸q①臥§歴︸o首P︶

o o

σ》

一〇乞鴇oEi邸の

§宕:蟹o邸ε①砺㊤.§ ^∩︵’︶﹄q ︶

おeε(おoσ》hP

一〇z毘①Ei邸の

お倉P︶︶〇一uうoσ︾σ︾PイF1

臥㊤>﹄⇒の︸o﹄器卜

融§

[June

。o o 9

,ト一.戯、8qN。き旨、崎ミ§δ§避§、ミ”融ミ誘哉醤奪§、ミ、ON雲

.〇一.畠.ら曾鴨§㌧も§ざミミO窯霞”h器§り趣霞さ篭選曙、肉。っH

.爲,q.NりqNら§“竃﹃寒ミ違■電、§軸書恥む選§鳶”許ミ曙跳醤さ笥§、ミ、H一。っ一

、Nり籍嚇§㌧−鳶ミ起竃き鍵輪浅、§︵嚢ミ喚窯霞賢魯§国︶違遷り“暑爵、§笥築ミ§ミ曙哉謹さ葛選ミ、。う8一

.ωoZ

一

眉も︻眉m

ヨリo︻宕m

渥一㊤︻弓m

三も︻弓m

ロ唱Φ[ヨo自

屓一〇=5qコ

泪一①=5ρ自

oう

のqo窟980

.■.β笥

.■.m

,ρ.pq

,口.qo

.ρ.ρ⇒

.臼.q⇒

.臼.m

︵蕊曾誌践窯二ε㎝。一意↑︶。う㊤︻潟↑葛壱boε[房自o。台℃省ερo。ρ濤g8ヒo窪[雲o窟身80.︵50の ℃壽、翁。δゆ漕リミミ

の9導の℃9眉P㊤ε 一〇 ︸ 邸琶∩

”30一①ρ℃8の娼

.O。っ℃鵠等.O。o.象、等籍、旨●忘§、属蘭書襲o§謹勘ミ”ミミ§喬り軌書、認O

z鴇①9邸の

z鴇㊤日邸の

z器㊤eoの

z鴇㊤E⋮縄の

薯q

A “

αq 唱θ

α国ε

一唱■一﹄o煽 hΣお

ωoり一℃邸国

1 置

”の8H50の

︵Io聖曽鵠q,醤嵩H 象o 謡一哺喫﹄日’ミ霧窯艶邑

︵Io喫簡騎o﹄篭Φ 幅一 貸FQ 醤9喫㊤・鴨の喫鴇罠o竜,一 ・麓

目oAhω三∈ ︵o τoの 哩の 嚇帽 醤 唱 、o 甲軸で ミ蓄遷> 唱 ぺ一 偽§襲Σ屈s

bρ

=応h﹄〇一“旨oqoの.ヨ 宕﹄ 壁O R超 B9 心一 嵩ゑρの・鴇信①Gニニ1の k憂碧§

謡矯鵠℃鴨Ioら9軸餐竜麹① ^℃§一〇唱39

目’qo欝㊤℃ ■目o酔戸.り筋田⑥昭総超 く︾﹄㊤ 曽① 目 ≒山■一ミ.9噸・8§δ罷

ひ一

℃員面の①のの師一〇=鳴h﹄〇一ロコ ︵■ loo 哩Ω司 黛O qoの禽豊

‡二5目■ o σ①

触亀暑δ、塞Dδ§ぺ■謹。弩醍−蒸寒ミO.窮ゆδ還還、ミ寒ミO睾き遣ミ§零曙。㊤.咽︶。層りg。屓一賃o改の㊤bo 尾 台 む>ヨの£こo① ︻ 馨 ㊤ε

礁の鵠9①色8勢g名=。コs[孚男σ①の一=o[㊤旨一。召あ㊤bρ訂3︸oむ>舅の⇔哨の遷]塞ゆ阿むさS図。起属書響ミQ日

o︸邸罵O

o

改

㊤日8畠身h揃 お倉P︶︶ooOLO①σ︾一H

z鴇①日邸の

z鴇09鳴の

z器㊤目忙の

z鴇⑪⋮⋮帽の

寸 eq

ご98b∈σ》OOFく I I寸O l lOFll lo−ooOr→Oooo㊦LOLDLDH目

z詔o目oの

リミ 。q

o o

し) q

ζつ 日

O N

・ 卜”

Q マー Fイ

り hこ

し》 』q

じ》 q

こつ q

之器㊤∈ロコの

う o o

Uつ

マ o

ト

o o 一

Q O

Pミ⊃ざ(の

OZ器①ε燭の

oう

一

eq 寸 oO

q ㎝

o“ A

う ト・

Cつ UD

○ 卜

う o

○ ① oつ

σ》 一

σ、

σ》 σ》 o

寸 F4

一 〇Q 寸ご“ 寸 LO

o o

oう

o 寸

囚 マ

N

(しく》

h

{

眺

寸

q o

ト・

o

卜・

LDH 一

oつ

F→

→ Fイ

o

H

o o

C団

寸

O H

〇 一 〇

の ト

o oつ

oう

H

eq o

の

o oう

o ・尊

o 卜・

o

σつ

目

卜

』D

σD

OQ

〇

・ 寸 ひ】

つ ぴう

8 守一 一

oつ uう

o 卜・

一 Fイ

“ 『ぜ

q ピ》

D σD

イ o

《 cq

儀

A

眺

一

唱 一

o o

㌔ oつ

q OQ

①

卜

σ》 寸

cつ

恥

A

h

一 寸

う αD− oつ

H

Q rび

D σ》

》 “う一 一

H 一

H

F司

マ ー

㎝ cq

o

頃

o o

》 蝉 め

つ OD

o 卜

寸

一

一

守 800 0

倒

R 詰O H

一 一

一

く 一

o

寸 O N

つ F4 で

O H

一

4 一

O QQ

H

一

一

、 一

r一{ P→

o OQ

o o o

O F《

o o

H

・《 H

H

一

o o

一

O r》

8 自Fく r→

〇一

卜H

((( ((((

邸騨Qo ℃㊤}ヒの

.︵bo︶g雲.。属℃濤蒼︶50マ。D.8乞幅︵︸︶8卜.oZ幅︵㊤︶き露.の。之パ℃︶℃昌︵。︶目o寸.o≧鴨︵﹄︶口o台H

,ト一.画、O頃qN.ねk母、§§9ミ津﹄ミ島ミ謹ミ箱ミ潟哉霞.鷺〇一

.。oN,画.。うδ=梱旨<.さ萄§、属ミミNミ麟成§慧きミ琶頃選縞暑§爵.oqO卜

.ト一.畠

鴇眉一の焉あ8ρ5︸05“田占、﹄。意■︸〇一5月鵠号∩φ.P①受台のむヒお㊤bo邸3hおのぞβgo娼5鳶一。詰

のののののσ5の

OOO OOoo

z乞乞 渚之z客

oZ鴇o目鳴の

{ H 一 一 一‘

一 cq oう 寸 ゆ

おお(⊃ (

αD

QO

αo

OD

oo

OO

αり

qD

σD

OD

OD

oo

49

ON EMPLOYMENT AND WAGE−DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN:A SURVEY

1967]

50

・ HITOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS [June

differensials between different sizes of enterprises.

It is necessary at this point to present evidences that the existence of intra-industry wage

differentials is not illusory and to supply a measure of their magnitudes. We may proceed

for this purpose in two different ways. One is to refer to previous works done by others

and the other to provide fresh evidence of our own.

As to the former approach, it sufiices to mention the following two contributions. First,

Takizawa's work attempts at a Japan-U.S. comparison of both wage and average value productivities by industry, relying on the data taken from the Censuses of Manufactures of the

respective countries,16 His conclusion is simply that the magnitudes of their differentials in

Japan by far exceed the counterparts in the United States.

Second, Blumenthal has applied the analysis-of-variance method to the data from 1961

Chingin Jittai So g6 Ch sa [1961 Basic Survey of Wage Structure],17

To be able to say something definite concerning intra-industry wage differentials among

workers, one must take note of at least four discriminating factors: (a) industrial classification, (b) age distribution, (c) skill-mix, and (d) sex, education, and other sociological attributes

of the workers,18 It is perhaps only the second factor that calls for special comment, since

it ' is observed that the wage scale in a typical Japanese enterprise is upward-grading in accord-

ance to the age of the worker, Consequently, the work force distribution of smaller companies,

which shows frequently high concentration of young workers, undoubtedly yields a lower

average than a group with more symmetric distribution. In fact, Sumiya once argued that

there are no intra-industry wage differentials as such, for they are essentially reduced to

differences in age distribution of the work force.19

Blumenthal has discovered, by contrast, that "the inter-scale wage differentials are a real

problem in the Japanese economy and cannot be explained away solely by differences in the

age structure."20 Nonetheless, he finds that demographic factors (age and sex) have by far

the greatest "explanatory power" in terms of the coefficients of determination: they account

for as much as 74 per cent .of the overall wage variations. On the other hand, industry and

size explain about 19 and 10 percent, respectively.

Having ascertained that the workers with equivalent personal qualities (sex, age and education) receive unequal remunerations in different industries and size groups, the author pro-

ceeds to seek explanations. As a result of a covariance analysis, average productivity and

unionization are found to be significant: the elasticity of the former yielding 0.130 and of

the latter 0,111, both at average points of the variables; whereas the excess-demand factor

(unemployment) does not exert any visible effect upon wage structure.

As an evidence of our own, the problem of skill-mix will be taken up, for little attention

has been paid to the occupational wage structure in Japan. Unfortunately, not many materials

are at hand for carrying out the analysis, The data reported in the surveys on wage structure by the Bureau of Labor Statistics have been utilized for the United States, and those

collected by the Ministry of Labor through Chingin Ko z6 Kihon Chosa [Basic Survey of Wage

'16 Takizawa [48], Ch. 2.

IT Blumentha] [2].

18 In addition, the geographical location of the firm should be taken into account. However thls factor

has received little attention up to the present.

' 19 Sumiya [43], Ch. 5.

20 Blumenthal, op. cit., p. 60.

1967] ON EMPLOYMENT AND WAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN: A SURVEY

1

Structure] for Japan.21

It is hard to attain precise correspondence between the two countries on occupational

categories and firm sizes. With respect to the first point, the definitions of occupational titles

given in the appendices to the Basic Survey of Wage Structure have been compared with

those in Dictionary of Occupational Titles published by Bureau of Employment Security, U.S.

Department of Labor (in 2 volumes, 3rd ed., Washington, D.C,, 1965). In spite of the careful checking, the correspondence remains loose; for one thing, the occupational categories

employed in the American surveys are much finer than their counterparts in Japan. The

sizes of the firm are, on the other hand, measured by the total number 0L employees. After

the scrutiny, a sample of seventeen occupations have been chosen from eight manufacturing

industries. For the sake of simplicity, the computation has been confined to male production

workers. Furthermore, efforts have been made to select the years in as cyclically similar

positions as possible; for it is known that wage differentials tend to contract during the

business upswing and widen during the recession.22

It is clear from Table 6 that in all but three cases (Nos, 3, 8 and 13) differentials are

much greater for Japan.23 As for the three exceptions, additional computations have been

made to check the consistency of the results for other years. As Table 7 indicates, textile

printer (No. 3) and iron worker (No. 8) have shown relatively small differentials throughout

the years. By contrast, the wage differentials of welders (No. 13) are not particularly small

for other years. Eliminating welders from the exception list, we may conjecture as a reason

for relatively small differentials among the remaining two categories (Nos. 3 and 8) that each

of them consists of two heterogeneous occupations: (i) indigeneous ,skills cultivated by grassroots workmen and (ii) relatively modern skills introduced from Western countries since the

TABLE 7. INTERTEMPORAL CHANGES IN WAGE DIFFERENTIALS,

FOR OCCUPATIONS NoS. 3, 8 AND 13 (JAPAN)*

(Unit of Earnin s : yen)

* For occupational titles and sources, see Table 6.

21 The same series of surveys as used by Blumenthal [2]. The survey has been conducted annually

since 1948, but its title varies slightly from year to year.

22 See Reder [36]; Taira [46], pp. 98-lOO.

23 It is interesting to investigate why intra-industry wage differentials do exist in the United States.

However, this will be a topic for a separate research .

52 IuTOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF ECoNoMlcs [June

Meiji era.

It is beyond our present scope to prepare a theoretical framework for uncovering the

entire mechanism of the differential structure. However, one may list a few relevant hypotheses concerning this problem,

(a) Because of both technological and pecuniary economies of scale, the smaller firms

are definitely at a disadvantage. Consequently, in order to be competitive, they have

to rely heavily on cutting labor costs; that is, Iow wage rates are essential for their

survival .

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

Profits for the smaller firms often include remuneration for the management services.

The element of uncertainty is greater, the smaller the size.

The time horizon is likely to be shorter for the smaller companies.

The smaller corporations often maintain subsidiary relationships with larger ones.

This means that the one is not independent of the other. And,

(f) The quality of production machinery, as well as the quality of engineering technology,

is inferior in the smaller enterprises .

In any event, such marked contrasts between large and small firms are sufiicient to provide

a strong backing for the conventional treatment of the employment mechanism-namely,

dividing it into subsections according to the size of the firm.

IV. Survey of Selected Literature on Employment Mechardsm

(1) Supply of Labor

For a given size of population, it is suggested that the labor force comprises several subgroups, distinct in their behavior.24 The argument may perhaps be summarized in the following classification :

permanent

force

{(b) secondary

force.

Labor committment {(B)(a)

short-run

- -

A) Iong-run

The choice of occupation, of geographical location of work place, and the setting of time

to enter and to withdraw from the labor force, etc., naturally come under the heading (A).

The major forces which determine the long-run supply of labor to the manufacturing sector

are: (1) net increase in population and (2) change in the composition of the labor force.

Given population increase, the latter is primarily influenced by the expected future returns,

along with all the other non-pecuniary elements. If we define the discounted, current expected

returns as

EY= Jt* Yte rtdt,

o (t* being the time of retirement)

where Yt is the income at time t, and r is a discounting factor, then the long-run supply of

labor to an occupation A relative to B, say LA/LB, will be determined by the ratio of the

two expected returns. EYA/EYB. Tracing such a relationship, one will obtain a supply curve

of labor to A in relation to B. The slope and curvature of the function are determined by

individuals' non-pecuniary preferences. Moreover, to be more precise, we should also take

24 Umemura [54]; also, Tsujimura [50].

1967] ON EMPLOYMENT AND WAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN: A SURVEY 53

into consideration the distribution of EY over time, not only the absolute magnitude of it.

In actuality, however, recruiting for industrial employment a person who is engaged in

a traditional enterprise as head of a family involves more than just the expected Luture income.

He will naturally demand additional compensations for occupational adjustment, for training,

for a new residential place and the cost of transfer-although a portion of such additional

expenses will be covered by the sale of his old properties.25 Furthermore, the deficiencies in

information media may greatly hinder the process.

As for the category (B), the "permanent" Iabor for (a) is fully committed to work and

its size may be considered to be fixed in the short-run, provided that hours and intensity of

work remain constant. This last point could very well be dlsputed, but it seems not too

farfetched to take those two factors as given, since hours and other conditions of work are

other conditions of work are normally not at the mercy of individual works, at least for a

short period of time26. By contrast, the portion (b) is susceptible to cyclical fluctuations.

Umemura has noted that it is convenient to describe the behavior of the secondary force in

terms of two hypotheses: (i) additional worker hypothesis and (ii) marginal worker hypothesis.

The former refers to the behavior where labor committent is a decreasing function of real

income; according to the latter, on the other hand, an additional employment is an increasing

function of job opportunities27

Labor Partitipation Rates

With the above discussion in mind, Iet us take a quick look at the actual record of labor

supply since 1945. The most thorough research in this area has been done by Umemura.

By using the investment-GNP ratio and the growth rates of GNP as standards of reference,

Umemura divides the whole postwar period (1945-62) into three stages: the recovery stage,

1945-51; the period of gestation for future growth, 1952-55; and the period of accelerated

growth, 1956-61. The trend of increase in the labor force matches nicely witn this staging

of development. The labor force as a whole increased at 2.8 per cent per annum between

Jnne 1950 and June 1955, whereas it grew at 1.5 percent per annum between June 1955 and

June 1960, both adjusted for seasonal and cyclical variations. The decline of the rates from

the former to the latter periods was much sharper for the female labor force (from 3.5 to I .O

percent per annum) than for the male force (from 2.4 to 1.8 percent per annum),28

The trend values of labor participation rates since 1949 also registered an umTlistakable

peak during the years 1954/55; the increase was particularly pronouncing for female labor

force. In other words, Iabor participation rates were in a parallel relationship to the increase

in real income per capita during the earlier period. This is apparently to fly in the face of

theory. Umemura thinks the reason for this contradiction lies in the extremely limited job

opportunities immediately after W.W.II. Put differently, the participation rates gradually

25 This point is elaborated on the basis of empirical data by Murakami-Kubo [19]. The minimum

amounts of income sufiicient to induce farmers to move out of agriculture have been estimated by Masui

[14], p. 51.

26 "...since universal perfect competition is consistent with fixed hours of work in production, each

worker is subjected to a constraint which, in general, prevents his adjusting the supply of his labor ' to

the going wage-rate. Consequently, his own valuation of his marginal factor may fall short of, or exceed, that of the market." (Mishan [17], pp. 210-11). Mishan thinks that this "indivisibility" of labor

supply accounts for the upward increasing supply curve of labor for the industry as a whole.

27 Umemura [54].

28 Umemura [56], p. 108.

54 ' . HITOTSUJ3ASHI JOURNAL OF ECoNoMlcs [June

moved up during the iperiod ds the accumulated excess supply decreased with the increasing

demand for labor.

After 1955, the participation rates went down steadily, contributing significantly to the

decline in the rate of change in the labor force, as noted above. The rates for males over

15 years of age, which stood at 85.7 percent in 1955, declined slowly until it hit 84,5 percent in 1960. The movement of the rates for the female force (over 15 years of age) paralleled

roughly that of the male force, descending from the peak of 55.6 percent in 1956 to 53.8 percent in 1900. Umemura ascribes the remarkable decline of participation rates since 1954 to

the rapid increase in real income, as well as to the subsequent decline in multiple job holdings

during the period. He found, in fact, a strong inverse association between real income and

participation rates for this period (June 1955-June 1960).29

As a matter of historical background, Iabor participation rates have generally been declining

since the 199_O's.30 Their increase during the first and second stages of the post-war develop-

ment may have been due to a temporary distortion of this long-run trend, caused by the

postwar readjustments. Furthermore, it is worth noting that Umemura finds the general

pattern of movements in labor participation quite comparable to that of the United States;

the only modification seems to be that the participation of married women above 20 years of

age is much lower in the United States. This phenomenon may be explained by the difference

in the proportion of women classified as "unpaid family workers" in both economies.81

Distribution of Labor Force

The shift in distribution of the labor force among different sectors of an economy is one

of the significant features in economic development. The overall growth in GNP can actually

be separated into three factors which are responsible for the resulting growth rates: change

in gainfully employed population, increase in aggregate output per worker, and growth in

average productivity due to transfer of workers.B2

The most noteworthy redistribution of labor force has been the shift from agricultural to

manufacturing sectors. The annual exodus of labor force from agricultural sector is estimated

to have been in the order of 170,000 to 210,000 for the Meiji period, 180,000 to 240,000 during

the period between the two World Wars, and over 400,000 to 500,000 after W.W.II. It is pointed

out that that labor exodus in Japan ' has been fairly stable (with a slight upward trend) in the

pre-W.W.II. years, making a: striking contrast with the postwar days.s3

The actual magnitude of the exodus is associated with relative expansion of the second

and the tertiary sectors of the economy vis- -vis agriculture, so that it cannot be entirely free

from the influence of secular fluctuations.s* However, the stream of transferring force has

moved always in one direction; recessions have merely caused slowing-down of the outflowing

stream, but not the reversing of the current itself.35

29 Ibid., p. 110. The participation rates

for male workers (x) are related to per-capita consumption

expenditures (y) as follows: x = 90. 449 - . 026y (R2 = . 957).

s9 Umemura [57].

sl Umemura [55], pp. 111-12.

s2 Ohkawa-Rosovsky [45], p. 579ff.

33 Umemura [5l], Ch. 8; cf. Namiki [23], pp. 151-54, 166; a]so, ditto., [22].

84 Minami-Ono [16]; Umemura [56], pp. 93-96.

35 The reversal of the manpower current was said to have been frequent (especially L0r female labor) in

the prewar period. See, for example, Sumiya [45].

1967] ON EMPLOYMENT AND WAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN: A SURVEY 55

Overemplqyment a'id Labor Sulppy

It has been long claimed that unemployment in Japan is not only small in quantity but

also insensitive to secular fluctuations. In terms of the short run, one may note the following

three points in this connection. First of all, Umemura has shown that the rates of unemploy-

ment are by no means constant through time. By applying a relatively simple method of

dividing seasonally adjusted series by trend series, he has found that the unemployment data

could serve as a business indicator despite its small amplititude.s6 This indicates that the

labor market is functioning, at least in part, as the text book claims it should. Secondly,

one may note that the size of the labor force is partly a function of job openings, and it

shrinks when demand declines. Thirdly, it is observed that unpaid family workers in both

agricultural and non-agricultural sectors do increase during the recession, absorbing the workers

who would otherwise be unemployed.

The last of the above observations takes us to a long-run perspective: how to explain the

absolute level of unemployment, which is second to nothing in its magnitude. A hypothesis

is that there is "overemployment," or low-income employment, both in agricutlture and in

non-agriculture.s? The social framework in which this mechanism operates is the system of

self-employment. This is typically found among farmers (small landholders), retail merchants,

artisans, and owners of small workshops. It is conceivable that those who come under this

category do not maximize their profits but perhaps maximize total product or, alternatively,

total utility of income.

As a matter of evidence, the total man-hours of labor for the average farming household

are calculated to be 6,000 to 7,000 hours per year, in contrast to 3,200 to 3,500 hours per

year for the average househoid of industrial workers residing in metropolitan areas.B8 Furthermore, the rate of (wage-equivalent) remuneration of the farmer is, on the average, a half of that

of the worker. Similar earnings-differentials are found among retailers' or artisans' households vis- -vis industrial workers'.39

It would be legitimate to call the "self-employed" sector "traditional" only in the following

sense: that the modern day household has been separated from enterprise in terms of

bookkeeping and of legal arrangements, whereas such separation is exceptional in this sector.

One should note that being traditional is not equivalent to being irrational.

Tw o Types of Supply Decisio n s

At this juncture, one cannot overlook an important question which has rarely been discussed by theoretical economists: who is the supplier of labor force ? Is it primarily an individual decision to enter the labor force; or is it rather a familial decision-making that is

relevant? This question is by no means superficial in an economy where a large number of

agricultural, service and even part of manufacturing production are in the hands of "family

enterprises."40 Members of a family who are engaged in economic activities in this manner

seldom regard themselves as "workers" and do not receive pecuniary compensation as such.

36 Umemura [53].

8T Ohkawa [30], pp. 206 ff., 226 ff. and 295ff.

38 Noda [24], p. 145. Actual measurement of the magnitude of overemployment is attempted in the

same volume where Noda's contribution is found.

s9 Umemura [55], pp. 97-101.

40 For a theoretical treatise on the behavior of agricultural household in this connection, see Nakajima

[20].

56 HITOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF EcoNoMlcs [June

This explains why they may be quite willing to work at the point where average, instead of

marginal, productivity of labor is equal to the rate of earnings.4i An empirical investigation

by Takahashi on agriculture in Kyilshi area has shown that the labor input has a maximum

point where average labor productivity is equal to the wage rates of agricultural day laborers.

According to him, however, the determination of the actual level of the input is affected by

the general standard of consumption in the surrounding region as well as by the opportunity

of side-employment.42

In this connection, Tsujimura has argued, on the basis of increasing marginal disutility

of labor and decreasing marginal utility of real income of the household, that the schedule

of labor supply is necessarily downward sloping with respect to wage rate.+3 In other words,

he thinks that the substitution effect between income and leisure is overwhelmed by the income

effect. A comprehensive, econometric investigation on this point is attempted by Obi and

others, by utilizing cross-section (family expenditures) data; they observe that the introduction

of habit formulation as a shift parameter yields satisfactory results.44

Signs for a Change

There have been growing indications that the situation is changing. By 1960, the growing demand for labor has reached the stage where recruitment of young "graduating" forces

did not meet the industrial need of labor. Perhaps the best indicator of the change is the

narrowing inter-firm wage differentials in new entrants' wages (see Table 8). Some natural

consequences of this are: (1) that structure of agrarian economy is facing a transformation;

i.e. (a) the rate of change in the trend value of agricultural labor force has turned to negative after 1954,45 (b) more and more small landholders are engaged in side-employment and,

in some cases, farming becomes a minor occupation, and (c) the market for new agricultural

labor (or young generation farmers) is getting tighter. Moreover, (2) the numbers of city

craftsmen, servicemen, peddlers and the like are now gradually declining and their wages

substantially increasing.46 In Ohkawa's terminology, this is the stage of "semi-1imited" supply

of labor.'7 At this stage of development, excess demand for labor begins to appear on the

stage, although a considerable portion of the overemployed persons may still remain to be

absorbed. Consequently, not only capital widening but capital deepening will take place.

(2) Demand for Labor and Wage-diffierential Structure

Several alternative explanations may be presented for the wage differentials in question.

For instance, the intra-industry wage differentials may be ascribed to: (1) technological differentials, such as those in capital intensity or in labor coefficients, (2) institutional barriers, such

as employment tenure or union activities, which are relatively concentrated in large-scale firms

41 The same idea is expressed by Ackly [1] in connection with the Italian economy (p. 548). According

to Umemura, the idea of family-based decision making should be credited to a Russian economist Chayanov

(The Theory of Peasant Economy, Homewood. Ill.: Richard D. Irwin, 1966), i.e. to his "lohnarbeitlosen

Wirtschaft" (Umemura [52]). See also Mazumder [15], where the author develops an idea akin to the

one above.

+2 Takahashi [47].

43 Tsujimura [50].

4 Obi, Ozaki and Sano [25].

+5 Umemura [5l], pp, 138-45.

46 Umemura [56], pp. 120-31.

d7 Onkawa [34].

1967]

ON EMPLOYMENT AND WAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN: A SURVEY

57

TABLE 8. ENTRANCE WAGES OF NEWLY GRADUATING JUNIOR-HIGH BoYS*

(In Current Yen)

* Monthly earnings.

Source: Originally based on Rodosho, Shokugy Anteikyoku (Employment Security Bureau,

Ministry of Labor), Shinki Gakk SotslLgy6sha no Shokugy Sh kai Jo ky oyobi Shoninkya Ch sa

Kekka [Annual Report on the Survey on Employment and Entrance Wages of the Newly Graduating Labor Force]; Cited from Nakamura [2l], pp. 69-70.

(after ¥V.W.II), (3) difference in quality of labor, (4) production agents' behavioral character-

istics which have hitherto been ignored, and (5) dynamic forces in action. The first two

will be the topics of the following p ges,

Labor Productivity a'id Capital Intensity

Komiya and Uchida have carried out a three-way analysis of variance on two selected

industries, textile and non-electric machinery for the year 1958; they found that labor coefficients (labor-output ratios) are significantly different according, among other things, to the

size of the firm. Their conclusion is that "[t]here is a need to define the sectors of inputoutput analysis not only on the basis of major products but also on that of the size of individual units of production."48 One may be inclined, on the strength of this finding, to argue

that wage differentials are -a--measure of_the extent..t( which_ tech lQlogical circumstances create

differences in labor-output ratios.49 However, there is no a priori ground that different levels

of average productivity should be directly associated with different levels of wages so long as

we assume homogeneous labor and competitive markets. It is necessary to introduce some

concurrent factors, institutional or otherwise, which prevent wages from being equalized.50

48 Komiya-Uchida [10].

d9 See also Blumenthal [2], pp. 64-67.

50 In the same vein, an implicit assumption underlies Wolfson's attempts to explain geographical wage

differentials by the difference in productivity. Namely, the supposition is that agricultural workers are

not capable of moving from one place to another depending on the prospect of climate, which is a major

factor in deciding the success or failure of crop production. My argument is consistent with a finding

of his , that the coeficients of determination become smaller when the area is divided into three homogeneous product regions. Shinohara's work indicates also that the association between wage structure

and average labor productivity tends to be weaker, the more homogeneous is the industry-mix he chooses.

See Wolfson [59], pp. 249-51 and Shinohara [40], p. 35.

58 HITOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS [June

In contr st to the wage fioor which is set by the supply conditions, it may be contended

that the "ceiling" of the wages is fixed by the firm's ability to pay. Accordingly, the focus

of the discussion shifts from labor to capi tl and product markets. Miyazawa and Shinohara

have recently presented a hypothesis which attributes wage differentials to the differences in

average productivity which are, in turn, explained by the differentials in capital intensity, due

to the imperfection in capital markets.51 They have independently demonstrated that the

limited amount of capital fund has been distributed in such a manner that larger corporations

have acquired bank loans relatively easily compared with smaller competitors. The stronger

financial position made it possible for the former to introduce relatively capital-intensive

methods of production and hence higher levels of labor productivity. This is in essence the

explanation of the persistent supremacy of large firms over small ones with respect to their

abilities of pay. In other words, a high level of capital-1abor ratio is associated with a higher

level of average productivity of labor, which in turn explains wage differentials by size of the

firm. In Figure 3 fs and fL represent productivity functions for small and large firms, respectively. The figure appears to explain why there are wage differentials even in equilibrium

(WL > ws) .

FIG 3, HYPOTHETICAL PRODUCTIVITY FUNCTIONS

rN

fL

4 f,

IJ,1,

fs

lpS

is

N

Miyazawa-Shinohara's capital concentration hypothesis is, in a sense, a modified version

of the institutional barrier theory, since they seek to ascribe the differentials in capital inten-

sity to the imperfection of the capital market. However, merely pointing to imperfection in

the capital market is not convincing as a valid explanation for persistent intra-industry wage

drfferentials. It is not explained, for one thing, why a rational businessman wishes to incur

higher costs when cheaper labor is available at hand. In order to complete the circle of logic,

one must introduce one or more of the following factors: (i) the differential structure of

product prices; (ii) the heterogeneity of labor; or (iii) different degrees of union pressure

according to the size of the firms. For, so long as competitive forces are in action, the final

51 See E.P.A. [9], Miyazawa [18], and Shinohara [39].

1967] ON Eh(PLOYMENT AND wAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN: A SURVEY 59

equilibrium will not be attained until both fs and fL m the above diagram share the same

tangent line (such as f's and fL)・ It should be observed in this latter case that we still have

different levels of both capital intensity and of average labor productivity, but no wage diff erentials . 52

In his rebuttal to the criticism, Shinohara has made it clear that he takes the imperfection of both product and labor marl{ets as given. His point is, he argues, that giant corpora-

tions in a rapidly developing economy are eager to introduce technology and to invest in

new facilities no matter what the current product price and factor costs may be, The capital

concentration on the basis of preferential financing has been the solution to the demanding

task of rapid growth, a byproduct of which is the inter-scale wage differentials.53 Unfortunately, this type of argument only ends in a tautology until an independent explanation is

given as to why there are imperfections in product and labor markets.

Unionism

This leads us to the problem of union pressure. It has already been noted in Section

III above that the wage variations due to industry and size differences are in part ascribable

to the strength of unionism. It is in fact true that organized labor shows heavy concentration

among larger establishments (see, e,g. Table 9 below), In addition, empirical findings suggest that there are significant impacts of unionsim on wage structure and money wage levels.54

TABLE 9. ESTIMATED RATES OF UNIONIZATION :

BY SIZE OF ENTERPRISE (1963)

(Private Firms Only)

!

Average

Source : ROdOsho (Ministry of Labor), Rodo

27. 8

35. 9

Kumiai Kihon Ch sa (Labor Union Survey), 1963.

Therefore, it seems safe to infer that the structure of union organizations and their strategies

must have been partly responsible for creating and maintaining intra-industry wage differentials

during the post-W.W.II days.

But would there be no wage differentials were it not for trade unions ?

One should note that there are indications that the differential structure did exist in per-

W.W.II period.55 At the same time, it is also well known that unionism was quite weak in

those days compared with the post-W.W.II period (see Table 10); furthermore, its strength

52

53

54

wage

Essentially the same point is made by Ito [7].

Shinohara t38]. Ch. 4.

Ono [35] and Watanabe [58]. Ono's paper investigates the influence of trade unions on inter-industry

differentials using the cross-sectional data for 1954. Watanabe, on the other hand, tests the Phillips-

Lipsey hypothesis on the post-W.W. 11 manufacturing data (quarterly, 1956 ;2). He observes that "in

general, the cost-of-living index or the rate of change of consumer prices plays an active role in wage

adjustments and this variable may well be interpreted as a strategic indicator of unlon power...." (p. 42)

55 See, e.g. Ohkawa-Rosovsky [271

HITOTSUBASIII JOURNAL OF EcoNoL(Ics

60

[ June

TABLE 10. MEMBERSHIP OF TRADE UNIONS, SELECTED YEARS

Sources: Pre-W.W.II period: Nihon R d Und -shi-r,.v [Collected Documents on Japanese

Labor Movement], Vol. 10, pp. 424-26; based on the surveys taken by Ministries of Interior

and of Welfare.

Post-W.W.II period: R dosho (Ministry of Labor). R6do Kumiai Kihon Ch sa (Labor Union

Survey) and Sorifu Tokeikyoku (Bureau of Statistics, Prime Minister's OfEce), R do ryoku Ch6sa

Hokoku (Monthly Report on the Labor Force Survey), June issues.

lay mostly in medium- or small-scale firms.56 This being the case, the story is hardly complete

until one presents a theory of wage-differential structure consistent with both economic rationale

and the forces of market mechanism.

V. Coneluding Remarks

It seems that the Japanese economy has not quite as yet passed the "classical" stage of

economic development insofar as labor supplies are concerned. The economy is presently in

the process of movmg from the "unlimited" to the "seml-limrted" phase (in Ohkawa's sense).

Schematically speaking, the economy may be divided into two sectors: traditional and capitalistic. The less advanced, or traditional, sector provides abundant supplies of labor with

comparatively low rates of compensation. In this type of socio-economic setting, the level of

manufacturing wages is largely supply-determined, the surplus of labor being conveniently

disguised" in the form of overemployment in the traditional sector.

''

The gist of our reasoning runs roughly as follows. We believe that both supply and

demand structures must be incorporated in order to clarify the persistence of the wage differentials according to the size of the firm. The relatively low level of wages sustained by

the semi- or un-limited labor supply has undergirded the successful management of small-scale

firms with relatively labor-intensive operations. On the other hand, Iarger firms are characterized

56 Sumiya [44], pp. 16 68. This, of course, does not leave out the possibility that the employers of

large firms were willing to pay above-average wage rates in order to protect themselves from unionization. However, the magnitude of the differentials was much too great to be explained away by this

f actor.

oN EMPLOYMENT AND wAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE IN JAPAN: A SURVEY

1967]

61

by a higher degree of capital-intensity which has been made possible, at least in part, by

preferential dealings in the capital market. The consequent economies of scale (both pecuniary

and non-pecuniary) and possibly advantages in the product market (price differentiation) have

endowed large-scale companies with better ability to pay and, as a result, they are potentially

capable of incurring higher rates of compensation, if necessary.

We shall contend that the above circumstances constitute the necessary condition for

conspicuous wage differentials by size of the firm. However, they are by no means sufficient. In other words, the abundance of labor supply and the higher ability to pay of larger

firms are consistent with the intra-industry wage differentials; but they do not offer the rationale

why large firms must pay higher wages. One may argue, in fact, that there is no such

necessity, unless there exist powerful institutional factors such as paternalism or unionism.

As for paternalism, it seems hard to believe that Japanese businessmen are so benevolent that

they pay higher wages wrthout any economrc Justuficatron

It is the existence of "internal" Iabor market within the firm that constitutes the sufficlent

condrtron In a modern manufacturing firm with diversified operations, not every job is exposed directly to the influence of the labor market at large (i,e. "external" market). In case

of slackening demand, for instance, the firm endeavors to keep the skilled workmen and to

make adjustments in the work force by putting tighter control on new entrants and/or discharging the unskilled. Akin to this view is the fact that labor as a factor of production is'

in many cases quite heterogeneous in quality, In particular, compensations to various types

of skilled labor should often be considered as overhead costs. Labor indeed is a special kind

of factor of production in that technological advance is naturally embodied in it; this fact

indeed furnishes the entrepreneurial incentive for investing in human capital by way of general

education, on-the-job training, apprenticeship program, etc., provided that regularity of labor

force wrthin the firm may be expected with reasonable certainty.57

Immediately following the War, Iabor economists in the United States tended to stress

the institutional peculiarities in labor markets and thus to de mphasize the market forces in

employment and wage determination. In more recent years, by contrast, the trend seems

to be reversing gradually. The excess demand adjustment mechanism underlying the PhillipsLipsey model, for example, postulates the effective functioning of the labor market. Clearly

one approach does not exclude the possibility of the other. It is mandatory that we elucidate

the function of the market forces in the given framework of institutional arrangements,

REFERENCES

[ll Ackley, Gardner. Macroeconoln'c Theory. N.Y.: The Macmillan Co., 1961.

[ 9]

Blumenthal, Tuvia. "The Effect of Socio-Economic Factors on Wage Differentials in Japanese Manu'

facturing Industries." Kikan Riron Keizaigaku (The Economic Studies Quarterly), XVII, l

(September 1966), 53-67.

[3] Enke, S. "Economic Development with Unlimited and Limited Supplies of Labour." Oxford Economic Papers (n.s.), 14, 2 (June 1962), 158-72.

[4] Fei, J.C.H, and Gustav Ranis. "Capital Accumulation and Economic Development." A,ner can

Economic Review, LIII, 3 (June 1963), 283-313.

5? Tsujimura has contended that difference in quality of labor plays a significant role in determining

the leve] of pecuniary remuneration. Tsujimura [49].

62 HITOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF ECOI 'OMICS [June

[ 5 J Fei, J.C.H. and Gustav Ranis. Development of the Il7bo' Surplus Econo'n)': Theory and Policy.

Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin, 1964.

[ 6 J Gleason, Alan H. "Chronic Underemployment: A Comparison Between Japan and the United States.>'

The Annals of._the Hitotsubashi Acedel7ry, X, I (August 1959), 64-80.

[ 7 J ItO, Mitsuharu. "NlJu ko o ron no Tembo to Hansel [Survey and Reflectrons on the Controversy

on Dual Structure]." In: Nihon Keizai no Kiso K z6 [The Basic Structure of Japanese

Economy], Tokyo: Shunjnsha, 1962, 169-9-1_9.

[ 8 J Johnston, John. Statistical Cost Analysis. N,Y.: McGraw-Hill, 1960.

[ 9 J Keizai Kikakuche, Keizai KenkOsho (The Institute of Economic Research, Economic P]anning Agency).

Shihon K z to Kigy kan Kakusa [The Asset Structure and Inter-firm Differentials]. Re

search Series No. 16, Tokyo, 1960.

[lO] Komiya, Ryntaro and Tadao Uchida "The Labour Coefiicient and the Size of Establishment in

Two Japanese Industries." In: Tibor Barna, ed., Structural Interdependcnce and Economic

Development, London: Macmillan, 1963, Ch. 14,

[1l] Leibenstein, Harvey. "Technical Progress,the Production Function and Dualism." Ba'lca IVazio'tale

del Lavoro Quarterly Review, No. 55 (December 1960), 3-18 [Reprint No. 177, Institute of

Industrial Relations, University of California (Berkeley)].

[12] Lester, Richard. "A Range Theory of Wage Structure Indust,lal and Labor Relatl0'Is Revretc'

5, 4 (July 1952), 483-500.

[13] Lewls, W. Arthur. "Economrc Development wrth Unllmrted Supplres of Labour The 14lanchester

School of Economic and Social Studies, 1954; reprmted in: A.N. Agarwala and S.P. Singh,

eds., The Economics of Underdevelopment, N.Y,: Oxiord University Press, 1958, 40O-49.

[14] Masul Yukio. "Noka ROdOryoku no KyOkyii Kakaku [On the Supply Price of Labor Force in

Agriculture]." In: K. Ohkawa, ed., Nihon Nogy6 ,10 Seich

in Japanese Agriculture], Tokyo: TaimeidO, 1963.

Bunseki [Analyses of the Growth

[15] Mazumder, Dipak. "Underemployment in Agriculture and Industrial Wage Rate." F_cono'ntca

XXVI, 104 (November 1959) , 328-40.

[16] Minami, Ry6shin and Akira Ono. "Noka Jlnko Ido to Keikl Hendo to no Kankel nl tsurte no

Oboegaki [Note on the Relationship between Agricultural Labor Mobillty and Business Cyclesl."

Kikan Riron Keizaigaku (The Economic Studies Quarterly), XII, 3 (June 1962), 64 7.

[17] Mrshan E J Survey of Welfare Economrcs 1939 1959." Econo'nic Journal, LXX, 278 (June 1960).

197-265.

[18] Miyazawa. Kenichi. "The Dual Structure of the Japanese Economy and Its Growth Pattern." The

Developing Economies, II, 2 (June 1964), 147-70.

[19] Murakami, Yasusuke and Machiko Kubo. "Wagakunl Noson Kozo i kansuru lchi-bunseki [An

Analysis on the Structure of Japanese Farming]." In: Y. Tamanoi and T. Uchida, eds., Nlji -

k z

no Bunseki [Treatises on the Dual Structure], Tokyo: Toy

Keizai ShimpOsha, 1964,

215-4 1 .

[20] NakaJuna Chihlro. "NOka no Shutaiteki Kinko to KajO ShngyO [The Equilibrium of the Farming

Household and Overemployment]." In K Ohkawa ed [29] 67 83

[2l] Nakamura, Atsushi. "Shonnkyu no Hendo to sono Eikyo nl kansuru Memo [Note on the Fluctua

tions of Newentrants' W. ages and Their Infiuence]." Keizal Bunscki [Economic Analyses],

No. 14 (April 1965), 61-76.

[22] Namiki, Shokichi. "Noka Jinko no Sengo JyGnen (The Farm Population in a Decade after the

War)." No gy

So g

KenkyiZ (Quarterly Journal of Agricultural Economy), 9, 4 (October 1955),

1-46 .

[23] Namiki, Shokichi. "Sangyo Rodosha no Kersel to Noka Jmko [The Formation of Industnal Labor

and Agricu]tural Population]." In: S. Tobata and K. Uno, eds., Nihon Shihonshugi to

No gy

[Capitalism and Agriculture in Japan], Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1959, 138-90.

[24] Noda Tsutomu. "Noka no Shotokuteki Chii [On the Income Level of Agricultural Households]."

In: Ohkawa, ed., [29], 137-50.

[25] Obi, KeiichirO, Iwao Ozaki and Yoko Sano. "Wagakunl nl okeru Shugyo Kiko no Kerryoteki Bun

seki (An Econometric Analysis of the Employment Strcuture in Japan: Report of the Research

Project on Enterprise [and] Household Behavior of Keio University)." Nihon R d Ky kai

1967]

ON E 'lPLOYMENT A 'D

vAGE-DIFFERENTIAL STRUCTURE lN JAPAN: A SURVEY 63

[ 96]

Zasshi (The Monthly Journal of the Japan Institute of Labour). I, 2-3 (May-June 1959), 5264 (May) and 46-58 (June).

O.E.C.D. TVages and I_abou' Mobil!ty, Supple'nent No. 1: Abstl'acts of Selected Articles. Paris,

[ Q7]

Ohkawa. Kazushi and Henry Rosovsky. "A Century of Growth." In: W.W. Lockwood, ed.. The

[ 28]

Ohkawa. Kazushi. "The Differential Employment Structure of Japan." The Annals of thc Hitotsu'

[ 99 J

bashi Acede"Iy, IX, 2 (April 1959), 205-17.

Ohkawa. Kazushi., ed. Kajo ShiZg v to i¥rihon No*g:y [Overemployment and Japanese Agriculture].

[30]

Toky0: Shunj sha, 1900.

Ohkawa. Kazushi. Nih0'1 Keiza! Bunscki [Analyses of the Japanese Economy]. Tokyo: Shunjnsha,

L3l]

Ohkawa Kazushl and Ryoshln Mlnaml The Phase of Unllmrted Supplles of Labor." Hitotsubashi

[32]

Ohkawa, Kazushi and Henry Rosovsky. <'Postwar Japanese Growth in Historical Perspective: A

Second Look." A paper presented at International Conference on Economic Growth, Tokyo,

[33]

Ohkawa, Kazushi and Henry Rosovsky.

1966.

State and Econo'nic E,tte'l・rise in Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965, 47-92.

1962.

Journal of Econo'nics, 5, I (June lq. 64), 1-15.

September 5-10, 1966. (Mimeo.) '

"Recent Japanese Growth in Historical Perspective."

Atnerican Econot'tic Revi('?c!, Llll, 2_ (May 1963), 578-88.

[34]

Ohkawa. Kazushi. "R d

[35]

Keizai K-enkyi (The F_conomic Review), 15, 3 (July 1964), 254-57.

Ono, Hisashi. "R d Kumiai to Sang. yokan Chingin Kakusa [Trade Unions and Inter'industry Wage

Differentials]." Kikan Ri,'on A eizaic"aku (The Economic Studles Quarter]y), XII, I (September

[36]

Reder. Melvin W. "The Theory of Occupational Wage Differentia]s." A,nc' ican F c' onomic Reviere',

[37]

XLV, 5 (December 1955), 833-52.

Reynolds. Lloyd and C.H_ Taft. 'Fhe Evolulton of Vagle Structure. New Haven: Yale University

[38]

[39]

[40]

[4l]

Kyokyn ga Han-sergenteki na Keizai (Semi-limited Supplies of Labor)."

1961), 15-9_6, _

Shinohara. Miyohei. Keizai Scic'h no K5z [The Structure of Economic Growth]. Tokyo: Kunimoto Shobo, 1964.

Shinohara, Miyohei. IVihon Keizai 110 Scich to ,Junkan [The Growth and Cycles in the Japanese

Economy]. Tokyo: Sobunsha, 1961.

Shinohara, Miyohei. Shotoku Bu'nl'ai to Chiltgi,1 K z [Income Distribution and Wage Structure].

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 19 55.

Shinohara, Miyohei. "Survey of Japanese I_iterature on the Samll Industry-with Selected Bib]i.

ography." (Mimeo.)

[42 ]

Steindl, Joseph. Small and 13ig Busincss; F conomic Problem of the Size of Fir'ns. Oxford: Basil

and Blackwell, 1945.

[43]

Sumiya, Mikio. Nihon '10 R do Mondai [Labor Problems in Japan]. Toky0: University of Tokyo

44]

Sumiya, Mikio. Nihon R d6 U,Ido sh! IA History of the Labor Movement in Japan]. Tokyo: YO.

[45]

Sumiya. Miklo. "Shihon to Rodo [Capital and Labor]." In: Nihon Jimbun Kagakukai (The Japan

Press, 1964.

shindO, 1966.

Cultural Science Society), ed.. Ho /.'en Isci [Feudalistic Remnants]. Tokyo: Yuhikaku, 1951,

123-36.

[46]

Taira. Koji. "The Dynamlcs of Japanese Wage Differentials, 1881-1959." Unpublished Ph.D.

[47]

Takahashl lrchrrO. "Jika ROd Toka no Mekanizumu [On the Determination of the Level of Selfemployment in Farming Households]." In: T. Matoba, ed., K'yasha ni okeru A-eizai to

iVogy (Economy and Agricu]ture in Kyushu). Tokyo: NOgyO Seg Kenkynjo (The National

thesis. Stanford: Stanford University, 1961.

[48]

Research Institute of Agriculture, Minlstry of' Agriculture), 1959, 137-91.

Takizawa, Kikutar . Nihon K gy ,10 A 6z Bunseki; 1¥rihon Chash A igy6 no lchi-henkyi [A Structural Analysis of Japanese Manufacturing Industries; A Study of Japanese Middle- and Smallscale Firms]. Tokyo: Shunjnsha, 1965.

HITOTSUBASHI JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

64

[49]

[ 50]

[5l]

Tsujimura, Ketar6. "Chingin Keitai to Sangy nai Chingin Bumpu [The Forms of Wage Payment

and Intra-industry Wage Distribution]." In: I. Nakayama, ed., Chingin Kihon Ch sa [Basic

Surveys on Wages], Tokyo: ToyO Keizai Shimp sha, 1956, 800-41.

Tsujimura, KOtare. "R6d Kyokyn ni kansuru Oboegaki (A Note on the Theory of Labor Supply)."

ILfita Gakkai Zasshi (Mita Journal of Economics), 49, 10 (October 1956), 15-26.

Umemura. Mataji. Chingin. Koy , Nogy

[Wages, Employment, and Agriculture]. Tokyo: Tai-

meidO, 1961.

[52]

Umemura. Mataji. "Kazoku Keizai to ROdo Shijd-Senzai ShitsugyO no Kenkyo (The Family Firm

and Labor Market-A Study on Disguised Unemployment)." Keizai Kenkya (The Economic

[53]

Umemura, Mataji. "Keiki Hendoka no ROdd Shij

Review). 5, 2 (April 1954), 112-19.

ni okeru Kansho Say

(Cushioning Functions

in the Labor Market during Business Cycles)." Keizai KenkyiZ (The Economic Review), 14,

1 (January 1963), 69-71.

[54]

Umemura, Mataji. "ROddryoku no K z5 to HendO (The Structure and Behavior of the Labor

[55]

Umemura, Mataji. "ROdOryoku no Kyokyo K z6 to Ky kyo Kakaku [The Mechanism of Labor

Supply and the Formation of the Supply Price of Labor]." In: M. Shinohara and M.

Force." Keizai KenkyiZ (The Economic Review), 8, 3 (July 1957), 227-33,

Funabashi, eds., Nihon-gata Chingin Ko z

[56]

[57]

no Kenkya [Studies on Japanese Wage Structure].

Tokyo: R d H gaku Kenkynjo, 99-136.

Umemura, Mataji. Sengo Nihon no R d ryoku: Sokutei to Hend [The Labor Force in the Postwar

Japan: Its Measurement and Analysis]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1964.

Umemura, Mataji. "Wagakuni ni okeru R dOryoku-ritsu no Choki Hend [Long-term Fluctuations

in the Labor Participation Rates in Japan]." In: Tokei Kenkyokai [Statistical Research Association], Shizgy ni kansuru Kc'nkyi [Studies on Employment], II, 1957, 5-17. (Mimeo.)

[58]

[59]

Watanabe. Tsunehiko. "Price Changes and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Earnings in Japan,

1955-1962." Quarterly Journal of Economics. LXXX. I (February 1966), 31-47.

Wolfson. Robert J. "An Econometric Investiagtion of Regional Differentials in American Agricultural Wages." Econowetrica, 26, 2 (April 1958), 225-57.

© Copyright 2026